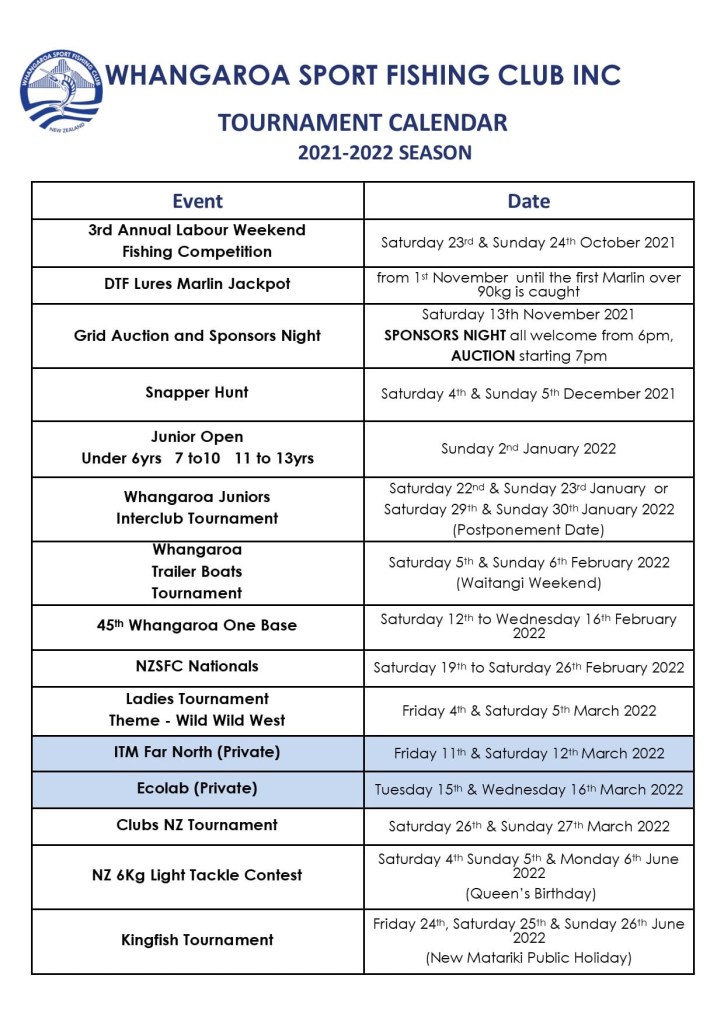

The schedule for fishing activities released by the local fishing club is attached. Make sure you are booked for the period.

Waterfront Retreat At The Whangaroa Harbor

The schedule for fishing activities released by the local fishing club is attached. Make sure you are booked for the period.

By Vincent O Malley, The SpinOff

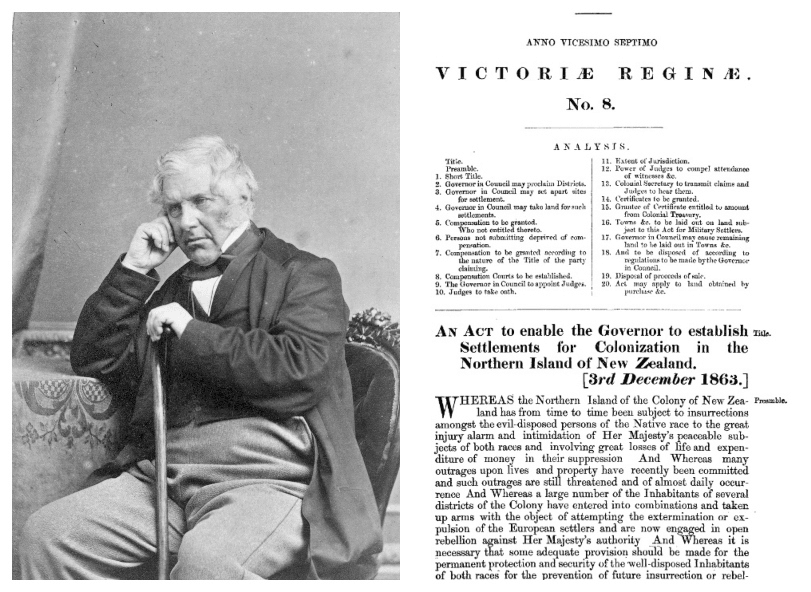

Passed on December 3 1863, the New Zealand Settlements Act may sound innocuous – but as Vincent O’Malley explains, for Māori communities it had devastating, lasting consequences.

Friday December 3, 2021 is the 158th anniversary of the passing of the New Zealand Settlements Act – the primary legislative mechanism for raupatu, the sweeping land confiscations that punished Māori for defending their lives and their homes.

It was accompanied by the Suppression of Rebellion Act, passed that same day, and a strong candidate for the most draconian piece of legislation ever passed in New Zealand, including as it did provision for summary execution of New Zealand citizens tried by courts martial for aiding or assisting in acts of “rebellion”.

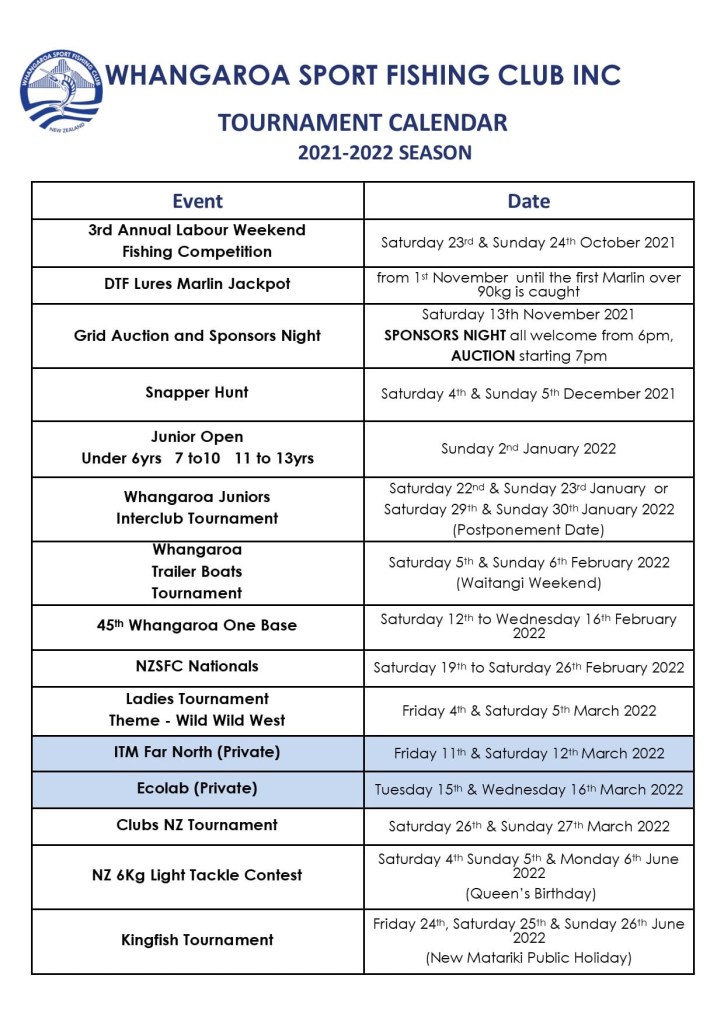

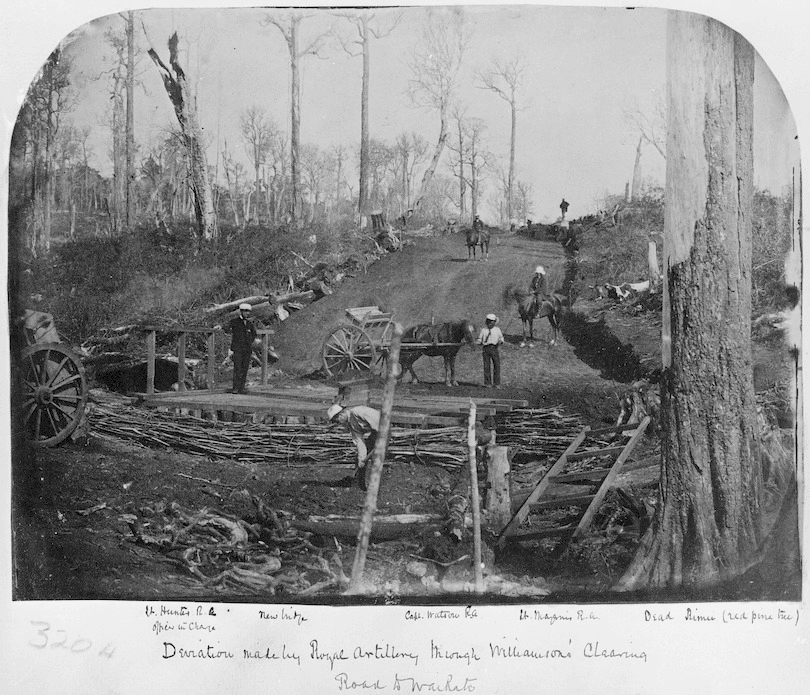

Governor George Grey and his ministers had drawn up their confiscation plans before invading Waikato in July 1863 and, by August, had begun recruiting military settlers who were to be offered a portion of the seized lands in return for their services.

Planting military settlers on some of the confiscated lands would ensure the conquest was permanent, while the sale of the remainder on the open market would pay for the whole scheme. Māori would effectively underwrite the costs of their own suppression.

But the confiscations were not without Pākehā critics. Former Chief Justice Sir William Martin pointed to the example of Ireland – where there had been a long history of land seizures – predicting that the subsequent “brooding sense of wrong” amongst the Irish, passed down from one generation to the next, would be replicated with Māori if confiscation was employed in New Zealand.

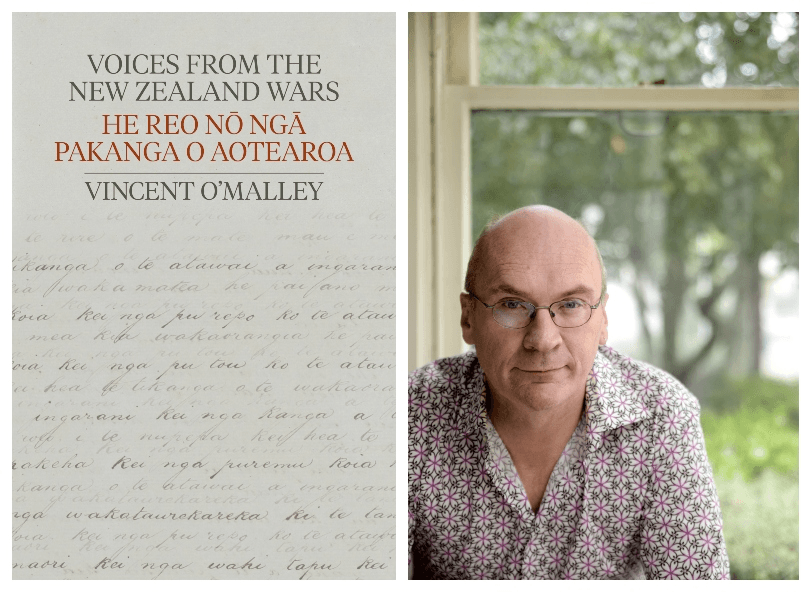

Canterbury politician and lawyer Henry Sewell was another critic. Writing in his private journal during the 1863 parliamentary session when these measures were being devised and debated, Sewell observed that the policy was corrupt, and advanced for the personal enrichment of various Auckland land speculators and politicians, notably Frederick Whitaker and Thomas Russell. Sewell’s forceful account, written by a political insider and member of the colonial elite, exposes the official rationale for the confiscation policy as (in his words) “a gigantic lie” – highlighting the value of the many first-hand accounts from Māori and Pākehā that appear in Voices from the New Zealand Wars/He Reo nō ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa. The following excerpts are taken from the full journal entries published for the first time in the book.

November 8th [1863]

I am horrified by two Bills brought in by Government worse than anything I could have imagined. One for authorizing the Governor to take Native Lands anywhere for purposes of settlement, a distinct violation of our treaty with the natives and of every principle which has hitherto governed our relations with them. And this not merely as affecting those in arms against us, but throughout the Colony including friendly as well as unfriendly. It is an atrocious proposal, which will if acted on probably involve a general rising of the natives throughout the Colony, and compel Great Britain to send a dozen more Regiments. The other measure [the Suppression of Rebellion Bill] is equally insane. It suspends all law throughout the Colony and authorizes the Governor to try by Court Martial any person suspected of favouring the Rebellion (as it is called) and to punish the suspected person by death, penal servitude or otherwise. The Habeus Corpus Act is to be suspended and there is to be no appeal from the decision of Military Courts. It is the production of madmen, but the Bills will be carried and the Governor will assent to them and there may be atrocities committed under them worthy of Judge Jefferys and the Bloody Assize. And there will be a faint echo of them heard in England, but nobody will trouble themselves about them; and these unhappy natives will be exterminated such at least is the power – and there is real danger of its abuse.

November 15th [1863]

[The Suppression of Rebellion Bill] establishes in short a machine for tyranny and oppression borrowed from the worst days of Irish History, from which the precedent is drawn. And this is to be used against a people to whom the Crown solemnly engaged that they should enjoy the privileges of British subjects – a people who are unrepresented in the Legislature and who understand nothing of our language or laws. The thing is a horrible invention of [Frederick] Whitaker, the Attorney General. It went through the House of Representatives with strong opposition, but the House submitted to it upon [William] Fox’s repeated assurance that the Bill was taken from an English precedent. The Suppression of Disturbances Act of 1833. Need I say that the statement is untrue? No man would have dared to propose such a measure to a British House of Commons. But here there is no lawyer in the House of Representatives, except those who are in the Government (there are four of them in the Ministry) and so private members were obliged to swallow the shameful misstatements of Fox and the others. I sicken when I think of these things. No doubt, as they say, they mean to use these powers mildly. Tyrannts always do, until something rouses them, panic, or some other passion and then of course such a seed produces its natural fruit. I am filled with horror, I cannot express my sense of indignation at the wrong done to this unhappy people whose doom may now be said to be sealed, for of course they will resist and resistance will be treated as rebellion, and bring with it confiscation of their lands, and final extermination. O that Great Britain would interfere! but I take for granted that she will look on patiently, leaving the Colonists to take care of themselves, and the natives. I write all this with shame and remorse as having been instrumental in placing power in the hands of men, whose first act is thus grossly to abuse it. Sir George Grey sits quietly at home, contented, if he can shift responsibility from his own shoulders.

November 17th [1863]

Under pretence of equity it is said that European as well as Native land is to be subjected to the same rule! but as the object is to plant European settlements upon Native Lands of course the inclusion of European Lands in the scheme is a flimsy pretext only intended to palliate the flagrant monstrosity of the proceeding. Friend and Foe are to be treated alike – Pas, Cultivations, Burying Grounds, all are to be swept into one great scheme of confiscation… And by way of insuring the utmost possible amount of danger this is to be done by forcibly expelling the natives and driving them to desperation…No doubt the Auckland Lawyers who have invented this scheme for driving the Natives to desperation have counted, not without good ground on being able to by means of it to exasperate them throughout the whole Colony and then applying to them the confiscation law, the whole country will be swept clear. First to drive the Natives to desperation, then to confiscate their Lands, is the obvious chain in this Auckland Policy.

The gigantic wickedness of this plot against Native Rights is attempted to be supported by an equally gigantic lie. The preambles of these Bills alledge in fact, that the Natives, the whole body of the Waikato Natives, and generally the Natives as a whole have been engaged in a conspiracy to exterminate the white settlers. It is a shameful falsehood contradicted by every paper which has been set before us.

Although the 1863 Settlements Act was clear that lands could only be confiscated if they were eligible sites for settlement, whole mountains, hills, lakes, swamps and other lands were taken across Waikato, Taranaki, Tauranga, eastern Bay of Plenty, and Mohaka-Waikare. In all, it added up to more than 3.4 million acres.

And despite repeated and unambiguous promises that Māori who did not take up arms against the Crown would have their lands guaranteed to them in full, confiscation was applied indiscriminately, even taking in areas owned by those who had fought on the government side.

A few Pākehā got very rich off the back of the confiscated land as New Zealand’s pastoral economy boomed. Other, often large areas were never sold or settled, and remain in Crown ownership to this day.

For Māori, the results of raupatu were shattering. In the two preceding decades, Māori had emerged as major drivers of New Zealand’s economy through the production of food for both local and international markets.

That economy was delivered a near fatal blow as cattle and crops were seized or destroyed, flour mills and homes torched, and the lands that had been key to this wealth confiscated. Generations of Māori were condemned to lives of landlessness and poverty as a consequence.

Passed nearly 160 years ago and largely unknown to most New Zealanders, the New Zealand Settlements Act left a devastating legacy that endures for many Māori communities today.

Voices from the New Zealand Wars/He Reo nō ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa by Vincent O’Malley (Bridget Williams Books, $49.99) is available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.

Divide the locals against each other, and conquer them by increasing internal strife that had been the hallmark of the British. They did this in India, and they did this in New Zealand.

Supplying harmful equipment was another strategy. The British missionaries supplied blankets infested with Smallpox to the Native Americans, wiping out over 80% of the Native American population. In New Zealand, they supplied the muskats to certain vulnerable tribes, thus encourages intertribal warfare that wiped out alliances, and combined Maori strength. Here is an except taken from the history of New Zealand.

Muskets (ngutu parera) quickly became much sought-after trade items in the old New Zealand. While the first muskets peddled by European traders were unreliable and slow to reload, the weapon ultimately changed the face of intertribal warfare. Tens of thousands were killed in the Musket Wars of the 1810s, 1820s and 1830s, and tribal boundaries were drastically altered. From 1818 northern Māori war parties armed with muskets attacked tribes further south. As iwi competed to obtain muskets an arms race developed.

These wars were often cited as the most negative consequence of contact and the reason why Māori needed the purported protection.

In 1830 Captain John Stewart of the brig Elizabeth made an arrangement with Ngāti Toa leader Te Rauparaha to ferry a taua (war party) of 100 warriors from his base on Kāpiti Island to Banks Peninsula. Te Rauparaha wanted to surprise his Ngāi Tahu enemies and avenge the killing and eating of several Ngāti Toa chiefs at Kaiapoi in 1829. Te Pehi Kupe had suffered the ultimate insult when his bones were made into fish-hooks. Te Rauparaha was keen to reassert his mana over his southern rivals.

In return for his services, Stewart would receive a cargo of flax. Although a business partner had been killed by Ngāi Tahu in 1824, Stewart’s motivation in 1830 was primarily economic.

The arrival of a European trading ship would not have raised any particular alarm among Ngāi Tahu. Stewart lured the chief Te Maiharanui (Tama-i-hara-nui) aboard by offering to trade flax for muskets. Once they were aboard, Te Rauparaha and his men seized the chief, his wife and daughter. Ngāti Toa warriors attacked and destroyed Te Maiharanui’s settlement, Takapuneke. Several hundred were killed and dozens enslaved.

The brig returned to Kāpiti with Te Maiharanui and his family held captive. Rather than see his daughter enslaved, Te Maiharanui strangled her and threw her overboard. Once on Kāpiti, Te Maiharanui suffered death by slow torture at the hands of the widows of the Ngāti Toa chiefs slain at Kaiapoi; his wife met the same fate.

Captain Stewart’s actions caused great concern among the missionaries, who were struggling to make progress in New Zealand. They felt that his participation in an ongoing dispute between tribes sent all the wrong messages to Māori about the effects of European contact.

The incident also highlighted the fact that New Zealand was a kind of judicial black hole. Governor Ralph Darling of New South Wales put Stewart on trial in Sydney as an accomplice to murder. In keeping with contemporary European attitudes, however, Ngāi Tahu were deemed ‘incompetent’ to act as witnesses because they were ‘heathens’. As a result, Stewart and his crew escaped punishment despite subsequent efforts to bring them before English courts.

The fact that no Europeans were killed in this incident meant that most Europeans took little interest in it.

Excerpt from https://nzhistory.govt.nz/

Māori responses in the early contact period were determined by well-established customs and practices. The notions of mana, tapu and utu were sources of both order and dispute in Māori society. They were practical forces at work in everyday matters.

Mana is often referred to as status; a person with mana had a presence. While mana was inherited, individuals could also acquire, increase or lose it through their actions. Rangatira (chiefs) in particular recognised the need to keep their mana as high as possible. Mana influenced the behaviour of people and groups, and was sought through achievements and successes. Māori vigorously defended their mana in everyday matters and tried to enhance it whenever they could. Sometimes the defence of mana required an excessive response to the actions of another.

Control of or patronage over European traders (and after 1814 missionaries) became an aspect of the pursuit of mana. Māori spoke of ‘our Pākehā’. Rivals could not be allowed to reap the advantages of access to these new arrivals without a challenge.

Māori life was also restricted through the placing of tapu on people and things. Tapu controlled how people behaved towards each other and the environment. It protected people and natural resources.

Almost every activity, ceremonial or otherwise, was connected to the maintenance and enhancement of mana and tapu. Crucial to this process was the concept of utu.

Often defined as ‘revenge’, utu has a broader meaning: the maintenance of balance and harmony within society. A wrong had to be put right, but how this was done could vary greatly.

Utu in the form of gift exchange established and maintained social bonds and obligations. If social relations were disturbed, balance could be restored through utu. One form of utu was muru, the taking of personal property as compensation for an offence against an individual, community or society. Once muru was performed, the matter was considered to be ended. The nature of muru was determined by factors that included the mana of the victim and the offender, the severity of the offence and the intent of the offending party.

If balance was not restored, a taua (hostile expedition) might become necessary. Even here there were levels of response. A taua muru was a bloodless plundering expedition, while taua ngaki mate or taua roto sought violent revenge for a death.

Māori were quick to recognise the economic benefits of developing a positive working relationship with Europeans. Trade and other Pākehā practices were accepted on Māori terms, with concepts of mana, tapu and utu playing significant roles.

Excerpt from https://nzhistory.govt.nz

Madhuban is happily located at the base of the rock formation of Ohakiri Pa, or, as the British settler’s renamed it – St Paul’s Rock. The rock is entwined in the Maori legend of the formation of Whangaroa Harbour, and is traditionally significant, a focus for mana in the surrounding area. It is a Maori citadel that is more impressive than many European fortresses. The site is culturally significant to Te Runanga of Whangaroa, to the descendants of early European settlers and in the Whangaroa region, and to all New Zealanders as part of their early history. And thus goes the legend of the Ohakiri…

Long ago there were two gods; Taratara was tall and handsome with many treasures and two beautiful wives, Okaha-hiria and Turou. Maungataniwha, who lived furthered up the Otangaroa Valley, was a jealous god who would use force if he could not get his way.

As Maungataniwha did not have a wife, he became very envious of Taratara, and decided to ask him for one of his wives. As he walked the ground shook for miles around. He stopped beside Taratara and asked for one of his wives. Taratara refused and so Maungataniwha went away disappointed.

Many months passed before he decided to ask again but Taratara again turned him down. Maungataniwha was furious and threatened to disfigure Taratara.

More months passed and Maungataniwha made a final request, so down the valley he thundered once more. This time when Taratara said “no” and laughed.

Maungataniwha became so enraged he lashed at Taratara, whose head flew from his shoulders across the Whangaroa Harbour to its present position- Ohakiri or St Paul’s.

Bits and pieces of Taratara were scattered far and near and lie on the valley floors of Pupuke and Otangaroa.

Maungamiemie was so distressed at the sight of her mighty neighbours fighting that she wept, and to this day her tears continue to flow in the streams that wind down to the waters of the Whangaroa Harbour.

This rock was later named as St Paul’s Rock by the British missionary settlers.

For more details, see the historical documents published by the govt of New Zealand.

The harbour was the scene of one of the most notorious incidents in early New Zealand history, the Boyd massacre. In December 1809 almost all the crew and 70 passengers were killed as utu (revenge) for the mistreatment of Te Ara, the son of a Ngāti Uru chief, who had been in the crew of the ship. Several days later the ship was burnt out after gunpowder was accidentally ignited. Relics of the Boyd are now in a local museum.

On 16 July 1824 on a voyage to Sydney from Tahiti, the crew and passengers of the colonial schooner Endeavour (Capt John Dibbs) stopped in Whangaroa Harbour. An altercation with the local Māori Ngāti Pou hapū (subtribe) of the Ngā Puhi iwi resulted in an incident where Maori warriors took control of the Endeavour and menaced the crew. The situation was defused by the timely arrival of the Ngāti Uru chief Te Ara, of Boyd fame.[2]

In February 1827, the famous Ngā Puhi chief Hongi Hika was engaged in warfare against the tribes of Whangaroa.[3] Acting contrary to the orders of Hongi Hika, some of his warriors plundered and burnt Wesleydale, the Wesleyan mission that had been established in June 1823 at Kaeo,[4] nine kilometres from Whangaroa. The missionaries, Rev Turner and his wife and three children, together with Rev. Messrs, Hobbs and Stack, and Mr Wade and wife, were ‘compelled to flee from Whangarooa (sic) for their lives’. They were conveyed by ship to Sydney, NSW.[5] During a skirmish Hongi Hika was shot in the chest by one of his warriors.[4] On 6 March 1828 Hongi Hika died at Whangaroa.[6] There is no actual evidence that Hongi himself plundered the mission; he was busily pursuing the enemy and being wounded. Nor is there any direct evidence to implicate anybody else [7] An alternate ideas was put forward by William Williams of the CMS. ” It appears beyond doubt, though our Wesleyan Friends are loathe to believe it, that it was their own chief, Tepui, was the instigator of the whole business”. [8] The local Ngatiuru had made the land available to the mission. For years the missionaries had lived amongst them and grown prosperous while the tribe still ate fern root.There was no prospect of the missionaries moving on and no prospect of them becoming acceptable neighhbours.They had not joined the tribe. They had set up their own tribe which was steadily wearing down the authority of the Ngatiuru leadership. [9]

Often referred to as the ‘Boyd Massacre’ or the ‘Burning of the Boyd’, the incident was dismissed as an act of Māori barbarism. From this perspective, there was little need to examine Māori motives. The event was etched into New Zealand folklore by European artists several generations after the actual attack. Their romanticised and often inaccurate portrayals embedded the incident in a frontier context resembling North America’s Wild West.

Under the command of Captain John Thompson, the Boyd left Port Jackson (Sydney) in October 1809 and arrived in Whangaroa Harbour in the far north to load a cargo of kauri spars. It was probably only the third European ship to visit Whangaroa. A year earlier, the crew of the Commerce had caused an outbreak of disease that killed a number of Māori. Ngāti Uru believed that a curse had been placed on them and viewed the next European visitors, those on the Boyd, with apprehension and suspicion. For his part, this was to be Captain Thompson’s first – and last – encounter with Māori.

Among the 70 people on board the Boyd was Te Ara, the son of a Whangaroa chief. Te Ara had been expected to work his passage as a seaman, but he ignored orders. He may have been ill, or, as the son of a chief, he may have believed that such work was beneath him. Whatever his reasons, he was flogged and denied food. When he arrived home and reported this mistreatment, his kin demanded utu.

Unaware of local feelings, Thompson and several crew members left the ship with a group of Māori to check out a stand of kauri further up the harbour. Once ashore they were killed and eaten. At dusk some Māori disguised themselves as the returning shore party while other warriors waited in canoes for the signal to attack. The assault was swift and decisive. Most of the Europeans were killed that evening, although a number escaped by climbing up into the ship’s rigging.

The next morning a large canoe entered the harbour carrying Te Pahi, a prominent chief from Rangihoua in the Bay of Islands who supported trade with Europeans and had visited Sydney in 1805. Shocked by what he found, he tried to rescue the frightened Europeans still clinging to the ship’s rigging. However, Te Ara’s relatives thought the matter none of Te Pahi’s business and killed most of the survivors. In a classic case of mistaken identity, Europeans would later blame Te Pahi for the tragedy.

The Boyd was then towed up the harbour towards Te Ara’s village and grounded on mudflats near Motu Wai (Red Island). The ship was pillaged of its cargo, with muskets and gunpowder being especially prized booty.

During the pillaging a musket flint ignited the gunpowder on board, causing a massive explosion that killed a number of Māori, including Te Ara’s father. Fire soon spread to casks of inflammable whale oil, and the Boyd burned down to the waterline.

Several Europeans survived both the initial attack and its immediate aftermath. They included Thom Davis (the ship’s cabin boy), Ann Morley and her baby, and two-year-old Betsey Broughton, who was taken by a local chief. Thom was spared because he had tended to Te Ara after his flogging and had smuggled food to him. The second mate was put to work making fish-hooks from barrel hoops, but when he proved incompetent at this task he was killed and eaten.

Rumours of the incident reached the Bay of Islands, and three weeks later the City of Edinburgh and other vessels to investigate. A Māori chief from the Bay of Islands who accompanied the European force negotiated the return of Ann Morley, her baby and Thom Davis. The taking of hostages secured the release of Betsey Broughton after a short delay.

Asked why they had attacked the ship, some of those involved said that the captain was a ‘bad man’. The whalers present blamed Te Pahi for the incident, even though the real perpetrators declared his innocence. Te Pahi’s pā, Te Puna, was destroyed by the European sailors, with considerable loss of Māori life.

This action resulted in civil war breaking out in the region, and in a final cruel irony, Te Pahi died of wounds received in battle in 1810. When Samuel Marsden arrived in 1814 to establish his Church Missionary Society mission, tensions still simmered. He invited chiefs from Whangaroa and the Bay of Islands aboard his ship, the Active, gave them gifts and asked them to ensure peace between their people.

‘Each chief saluted the other,’ Marsden wrote, ‘and then went around to each one pressing their noses together.’ They also assured him that they would never harm another European.

For some Europeans the Boyd incident put New Zealand in the ‘avoid if at all possible’ category. A pamphlet circulating in Europe warned sailors off the ‘Cannibal Isles’ – ‘touch not that cursed shore lest you these Cannibals pursue’.

Wises New Zealand Guide, 7th Edition, 1979. p. 508.

Acknowledgements : Parts of this blogpost have been lifted from Wikipedia

Not broken yet, this mirror of the morning,

The heart-shaped polished nephrite of the sea.

Oh, mirror of mornings, shield of steely twilights!

Cannot your look assuage and counsel me?

Dancers of the day press on, let fall their veils,

Rose burning on the circles of the waters,

No question blinds their upturned faces,

Never a green life shirring in the thickets

But knows some keyword, that its life is spent,

Death-dogged and secret, and a flash of wings,

But not perverse; not wholly malcontent.

And Pani holds aloft the beaded maize,

And tilts her jewelled basket of the moon

For all but him whose hopes ride out too far

On great white horses, in a nameless noon.

Shall none behold thee but the goddess daughters

Who look again and see themselves new-fair,

And burn across the skies, and light a morning

With the heavy candelabra of their hair?

Robin Hyde

Some of New Zealand’s famous are from our smalltown Whangaroa

Eric Rush (born 1965 in Kaeo) is a New Zealand rugby union footballer and a Rugby Sevens legend, arguably one of the greatest sevens players to grace the game. In a distinguished NZ Sevens career, which began in 1988 and ran until past his 39th birthday in 2004, Rush played in more than 60 tournaments, with the highlights being 2 Commonwealth Games gold medals and the World Cup Sevens victory in 2001. He was also voted Best and Fairest Player at the 1991 Hong Kong Sevens.

Robin Hyde (born 1906, died 1939) is now regarded as a major figure in 20th century New Zealand modernist literature. She is one of New Zealand’s greatest poets, and was also a renowned novelist and a ground-breaking journalist. Her most famous novel, the

semi-autobiographical “The Godwits Fly” was completed at Otawhiri Point, Totara North in 1937. One of her most well-loved poems is entitled “Whangaroa Harbour”.

Hiwi Tauroa (born 1927) was New Zealand’s first officially-appointed Race Relations Conciliator. Before he took up this role, Hiwi was prominent in many circles, as a member of the New Zealand Maori rugby team, the principal of Wesley College, the coach of the Counties Manukau rugby team, chairman of the Maori Broadcasting Agency Te Mangai Paho, as well as being the author of several books on various subjects. Hiwi lives with his wife Pat at Waitaruke.

Richard Parker is one of New Zealand’s most acclaimed ceramic artists. Winner of any awards, and with an impressive range of work in private and public collections worldwide, Richard Parker is often described as “a potter’s potter”. He has exhibited widely over many years, both in New Zealand and in Japan, Europe and the United States. His highly original and distinctive works are much sought-after by collectors and connoisseurs, both here and internationally. For many years he lived and worked at his studio on Omaunu Road, until moving to Kerikeri in 2009 to take up a teaching position at NorthTec.

Richard Mapp is one of New Zealand’s leading classical pianists. He made his solo debut at the age of 12 with the Christchurch Civic Orchestra. After graduating from Otago University, he pursued his musical studies in the UK. His Wigmore Hall debut was very well received and a successful career of solo and recital engagements in Europe, Scandinavia and North America followed. During his time in Europe, he recorded several times for the BBC and his recent release of the piano music of Enrique Granados received glowing reviews in the BBC music magazine. After returning to New Zealand in 1991 to live at Waitapu Bay, he co-founded the Bay of Islands Arts Festival and the Kerikeri International Piano Competition. He lived and taught music at Waitapu Bay until 2003. He is currently Senior Lecturer and Head of Piano Studies at Massey University in Wellington